The God of the Contrast

In my sophomore year of college, I had a particularly memorable spiritual experience that has transcended the twists and turns my faith journey has taken.

And it’s not what you’re expecting.

On something of an impulse, I accompanied a group of friends from my dorm for a night-time viewing of Interstellar, which was, at that time, the latest film by Christopher Nolan and Hans Zimmer.

In this film, a former astronaut is unwittingly recruited to command a last-ditch effort to save humanity by traveling through a wormhole that appeared out by Saturn. The plot leverages time and physics in a spectacularly mind-bending fashion, leaving viewers confronted with the subjectivity of our local experience. The end of the film is a fairly impressive twist leveraging a black hole–my favorite astrophysical concept–towards a beautiful, melancholic ending.

There’s no way for me to intimate the grandiosity of the film, its plot, or the ways it still makes me feel, but I can at least describe that first experience.

I remember virtually nothing about that day nor the events leading up to the viewing, but I vividly recall everything I experienced after the credits rolled. I walked outside in the cool Lynchburg night under the oppressive fluorescence of mall parking lights.

I looked up to a dark, light-polluted sky, spotted by a few stars.

I had nothing to say.

The word best approximating my experience in that moment is “worship”–a feeling of awe and utter helplessness at the staggering contrast between my fleeting existence and that of the Universe. I felt helplessly and incomprehensibly small, our solar system not even a blip on the cosmic radar.

And in that moment, I felt my intuitive knowing of God expand.

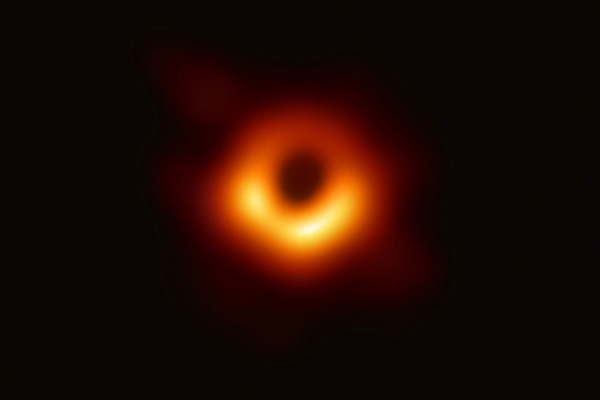

Last week, scientists around the world unveiled the first-ever image of a black hole’s event horizon, captured by an unprecedented network of telescopes spanning the entire planet. They focused in on the supermassive black hole at the center of M87, a nearby elliptical galaxy some 53,000,000 light years away–that is, it would take 53,000,000 years to get there at a speed of 186,000 miles per second. In the image below, you’re seeing light that’s taken 53,000,000 years to reach us, light that emanated from this point in the Universe long before humanity’s first ancestors walked the earth.

You’re seeing a solar-system-sized well of infinite gravity distorting space-time in ways that are really, really hard for our rather linear brains to comprehend.

It’s staggering.

What does any of this have to do with Good Friday?

Contrast.

When Paul exhorted the Athenians over their worship of an “unknown god”, he described a Creator in Whom and through Whom we have our being, a Divine Presence that is far more than a moody grandparent overseeing the machinations of our daily lives. In the words of St. Anselm’s 14th Meditation, “In no place art Thou otherwise than present.” Whether in the laughter of a child, the dividing of a cell, the exchange of electrons, or the singularity churning behind an unknowable veil, God is there.

“Thou art everywhere, and everywhere art entire.”

In first-century Palestine, in the womb of his mother, as a refugee in Egypt, a child in the Temple, a Rabbi in the synagogue, a prisoner of the state, as a man dying on an imperial torture device, in the experience of total forsakenness, and in the desperate cries of a grieving mother, the Divine was fully present.

Bringing the fullness of God to bear on our lives, in our world, is at the core of the Incarnation.

The notion of Jesus’ death having absorbed the anger of the Divine on our behalf has been dismissed by many of us as the violent projections of a hierarchical, punitive society. The cross is a difficult thing in every direction, particularly when the world seems to assume the penal model of atonement is the primary lens through which the crucifixion is understood. I don’t believe Jesus died on behalf of my sins or as a means of satisfying Divine wrath, but I do believe Jesus died at the hands of our wrath, at the orders of our Empire.

When I think of Good Friday, I see the God of the singularity utterly humiliated, hanging on a tree, demonstrating the love of God to the very ends of human experience while showing us that there is and always will be a better way. I see the God of space-time alone, bruised, and abandoned by the very ones she called “good”. In his humanity, in death, in suffering, in naked vulnerability, God is contrasted with all we think God to be, and the result is startling.

Humbling, even.

It’s a beautifully dark, wholly good Friday.